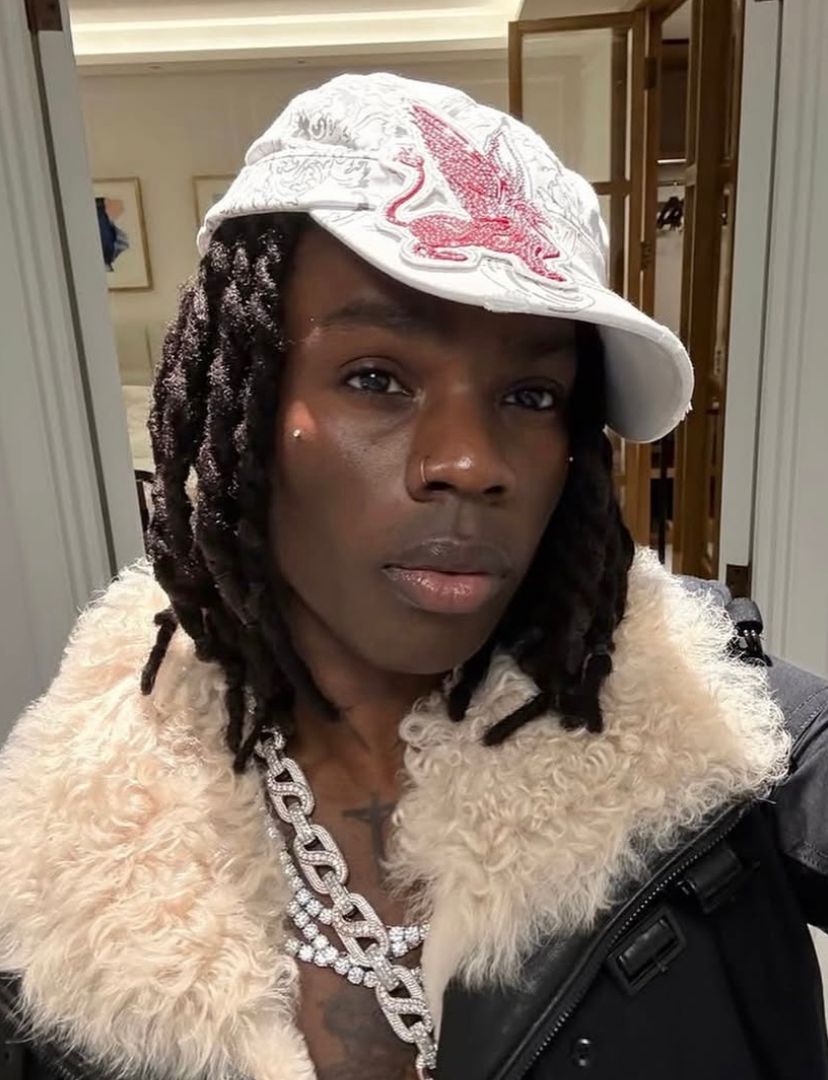

When Rema stepped on stage at Wireless alongside Drake, something in his outfit caught the eye of industry heads and casual fans alike: a sharp, military-style cadet hat, unreleased, untagged, and stamped with an emblem no one could yet name. The piece came from Souljier, a high fashion streetwear brand spearheaded and led by Nigerian designer and photographer Abdulbarr Logunleko, professionally known as Wallstreet. And it wasn’t available anywhere, at least not yet. This moment caught ours and the internet’s attention, leading to the need to know more about the unreleased brand and the person behind it.

Raised in Lagos and now based in the UK, Wallstreet’s creative journey didn’t begin with strategy or a moodboard, but by accident. While in secondary school, he walked into a photography club “just to avoid getting punished” for skipping extra-curricular’s. That accidental decision turned into practice. Then repetition. Then a lens, and a new way of seeing. By the time he moved to the UK in 2021, he had already begun designing graphics, not for commissions or income, but because “there could be better versions of designs out there.” A self-taught creative, he used YouTube tutorials to learn Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator. He was also heavily influenced by his uncle, a man who introduced Wallstreet to the tedious world of production and clothing design. His first public attempt at design was a rework of Wizkid’s Made in Lagos merch, and although this wasn’t a job, he posted it because, as he put it, “I wanted to see good art out there.”

That drive became the ethos behind Souljier. The brand’s name, a stylized reimagining of “soldier,” stands for “strength, resilience, and boldness.” He went into detail on what he hopes for the brand, particularly stating how he doesn’t want its pieces to just be worn casually, but to be statement pieces in themselves, something people would want to identify with. Even now, with multiple co-signs and a growing portfolio, he doesn’t consider himself a professional. “I still use tutorials,” he says. But his process is obsessive. When designing for an artist, he fully immerses himself with their work, as a way to enter into their visual headspace. “I watch their interviews, performances. I listen to only their music for at least two weeks straight.” His creative discipline is rooted in perfectionism, although it comes at a cost as he once fell out with a manufacturer for making too many changes to his designs.

“Time is a fallacy,” he says. “Take your time.” Wallstreet isn’t one to be swayed by hype or large exposure, his focus remains in creating high-quality art that resonates with people and has a lasting impact. He’s not here for the moment, but for the long game. His networking approach mirrors that same persistence. Every opportunity began with cold outreach: DMs to stylists, emails to artist managers. Many went unanswered. One that didn’t: Richie Igunma, aka SCRDOFME, a prominent Nigerian creative director. Wallstreet had emailed him two years earlier and received no reply. Then, suddenly, a message. Richie wanted design concepts.

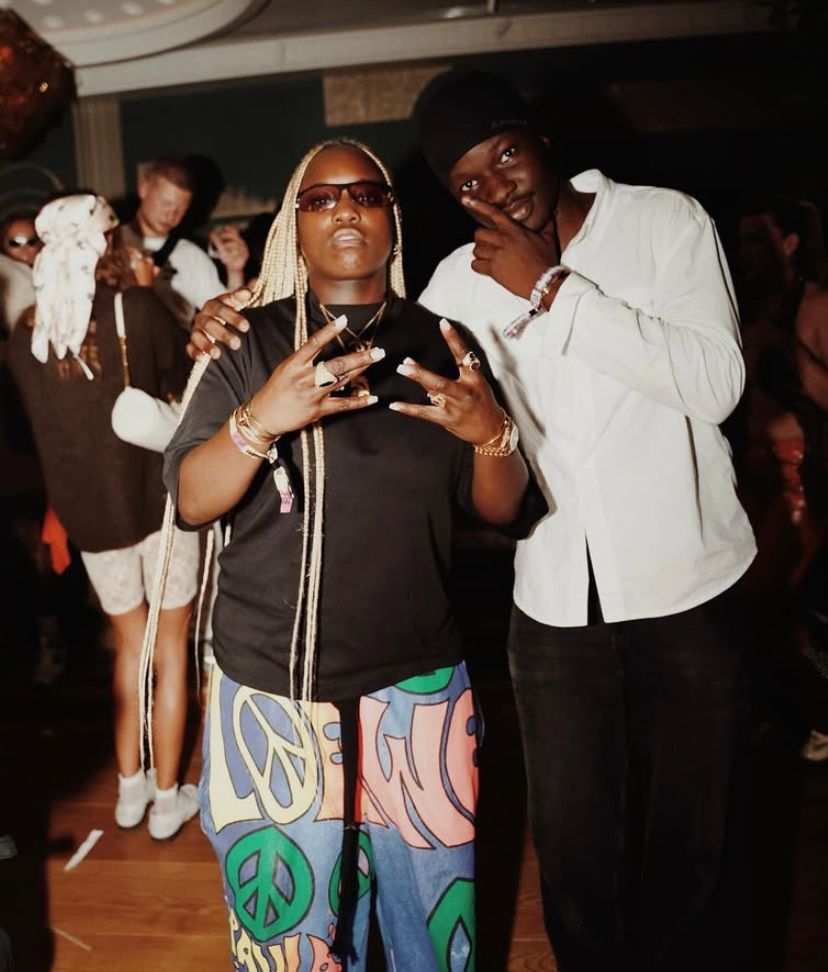

Another turning point came from Ireti Zaccheaus, founder of Street Souk and one of the most influential figures in the African streetwear space. She not only responded to his work, she offered feedback and support. Eventually, she invited him to document a Street Souk pop-up in London. Against his family’s wishes, Wallstreet traveled from Scotland to attend. His first meeting with Ireti, however, proved his dedication. Since then, he’s worked on many designs for Ayra Starr, Davido’s 5IVE tour merch, motion graphics for Rema’s HEIS tour, and many more. He also reconnected with Ireti, joining the Street Souk design team.

Wallstreet defines his own uniqueness. He sketches when ideas strike, sometimes waking in the middle of the night to translate a thought into form. He doesn’t present as overtly extroverted, and rarely seeks validation. Known to be both shy and headstrong, he values creative autonomy above all else, preferring to follow his instincts rather than bend to expectations. Though trying to shape an audience in the UK, his connection to his Afrocentric identity remains intact, something that is deeply embedded in his worldview.

In five to ten years, he sees himself as a forerunner in both fashion and photography. “Be unserious,” he says. “It allows you play around with ideas.” And yet nothing about his approach is unserious. Wallstreet, like Souljier, is built on intention. Built to last.